Charter Schools at Age 30: Can Facilities Keep Up?

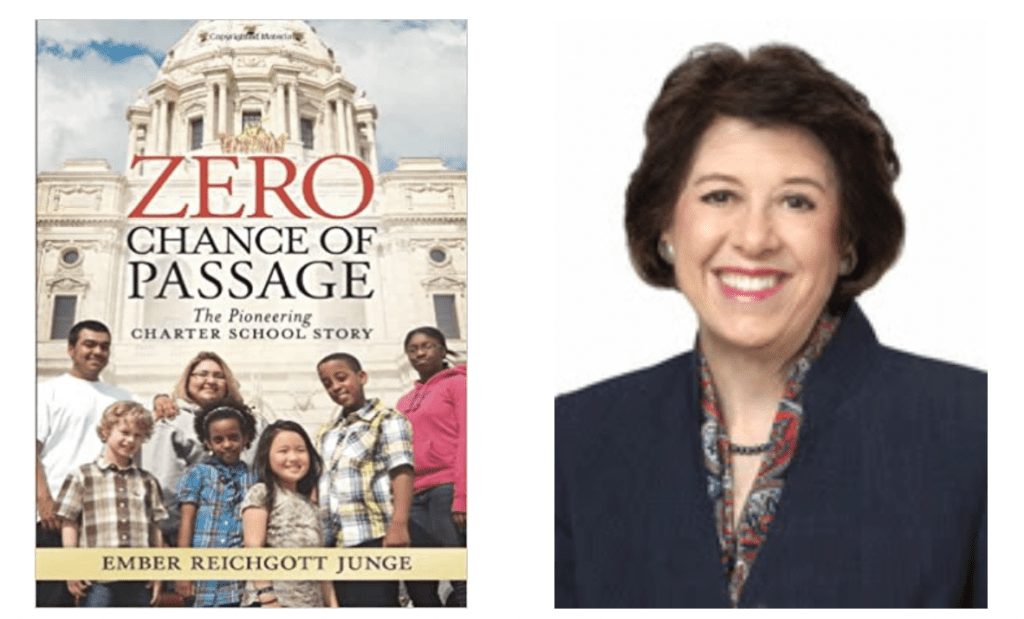

When former Minnesota State Senator Ember Reichgott Junge traveled the tumultuous journey to pass the first charter school law in the nation on June 4, 1991, the issue of charter school facilities was rarely mentioned in any debate. “Legislators assumed that charter schools would have access to existing school facilities or other buildings,” she recalled. But due to a variety of political and other reasons, that was not the case.

It was clear that charter schools needed financing and other funding to build the kind of facilities their students deserved. Without that, charter school leaders were forced to use limited operational funds from school funding formulas to pay debt on their facilities. That’s because under the charter school law, charter schools were not allowed to use property taxes for building and capital improvements as is allowed for traditional district schools.

Two pathways emerged to address the issue. Minnesota lawmakers recognized the issue early on and in 1997 created a new per pupil funding source for facilities called “lease aid” to help charter schools pay for leased spaces (up to about 90% of rental costs). Today 27 states and the District of Columbia provide some form of funding for charter school facilities, though only 12 of them explicitly include charter schools in the statutory language. (Three more states chose to exclude charter schools from their facility funding language.)

A state-by-state solution was therefore not sufficient as charter schools spread around the country. So about 20 years ago, an ad-hoc coalition of stakeholders spearheaded an effort to create a limited federal role in assisting charter schools to address this inequity and the twin challenge of acquiring and financing facilities. Given the lack of equal access to public capital funding under state law, those early advocacy efforts proved critical when, in 2001, Congress approved the creation of a $25 million credit enhancement “demonstration” program, the forerunner to the current Credit Enhancement for Charter School Facilities Program administered by the U.S. Department of Education. Over the past two decades, this program grew substantially and now provides over $500 million in grants for credit enhancement and revolving loan programs operated by nonprofit organizations and state agencies. These federal dollars are intended to help schools access non-federal capital to acquire, construct, and renovate facilities at market or below market rates. To date, the program has leveraged approximately $6.5 billion in private sector financing and leases for facilities on behalf of 837 charter schools nationwide.

Organizations were created like Charter Schools Development Corporation (CSDC), a nonprofit and Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) committed to working with new charter schools, which became a multi-grant recipient under the federal program. According to Michelle Prosperi, CSDC Chief Operating Officer, CSDC supports quality charter schools for underserved students by providing loan and lease guarantees, real estate development services, and direct lending.

One example of a charter school benefiting from the federal facility grant program is Paramount Brookside in Indiana. With nothing more than a charter in hand, CSDC took the early risk and purchased a 50-year-old 22,000 square foot former Masonic lodge for the purpose of converting and expanding this unconventional facility into a state-of-the-art educational campus incorporating many sustainable “green” elements. Students now enjoy a colorful, homey educational environment where curriculum runs the gamut from environmental stewardship to next-century innovation. For more details on the financing of this charter school see below.*

Despite all these advances in the chartering facilities arena over 30 years, studies show facilities to still be the greatest barrier to establishing and expanding charter schools. Unfortunately, there remains a lack of urgency at the state level to address this disparity. The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools ranks individual state charter laws on an annual basis against a “model law” based on 21 essential components of a strong charter school law. In 2020, for 17 of 21 components, many states received a rating of 4 on a scale of 0 to 4. However, for the sole component related to equitable access to capital funding and facilities, no states received a 4, and only 10 of the 45 states with charter school laws received a 3. According to their new report, “Charter School Access to District Bonds,” as of the end of 2020 only 5% of all charter schools have had access to local school district bond proceeds. That’s only 365 individual schools operating in only 4 states.

The bottom line is despite all of the great strides the charter movement has made over the past 30 years, there is still a void at the state level that federal policy needs to continue to fill. Ongoing advocacy efforts at the federal level remain critical until such time as every state’s charter school law receives a 4 out of 4 for providing equitable access to capital funding and facilities for charter schools.

Ember Reichgott Junge is the senate author of the first charter school law in the nation, and Board Vice Chair of Charter Schools Development Corporation. Michelle Prosperi is Chief Operating Officer of Charter Schools Development Corporation.

*Paramount Brookside Charter School: Converting a Masonic Lodge to State-of-Art Facility

With nothing more than a charter in hand, Charter Schools Development Corporation (CSDC) took the early risk and purchased a 50-year old 22,000 square foot former Masonic lodge for the purpose of converting and expanding this unconventional facility into a state-of-the-art educational campus incorporating many sustainable “green” elements.

The National Bank of Indianapolis (NBI) financed 75%, or $3,800,000 of the total project cost, leaving a 25% financing gap. As a de novo start up school, Paramount lacked any equity and needed to secure 100% financing to make their facility dream a reality. CSDC worked closely with a local CDFI to secure the sub-debt portion of the financing structure, but was declined primarily due to what they perceived as enrollment risk and concerns regarding the school’s unique educational program and model. CSDC has a commitment to working with new schools and pledged $1,300,000 in federal credit enhancement as the collateral needed to induce NBI to extend a separate loan to the school to be “equity-like,” and ultimately, financed the whole project. The school commenced operations in 2010 serving 370 students and today enrolls over 800 with 80% qualifying for free or reduced priced lunch and 77% identifying as BIPOC. The school has been recognized for closing the achievement gap regardless of income, received an “A” rating for five consecutive years and was awarded the 2018 School Excellence Award by the Indianapolis Urban League.

The Paramount facility affords learning opportunities at every turn by leaving many of the new and existing building elements exposed. For example, students are able to see how power is generated using five 40 foot, 2500 Watt wind turbines – the first charter school facility in the nation to use wind power as a source of energy at that time, observe the mechanics of an elevator, and actually see beyond the paint on the wall by looking inside it. Paramount is a powerful example of green initiatives at work in the educational setting. Green practices reduce the carbon footprint of the school every day that the school is in operation. The following features outline many of these green efforts:

- An onsite wind farm directly offsets electrical expenses

- Recycled carpet squares keep acoustics low while keeping all major surfaces green

- All students compost food from school lunches and this compost is used to feed the yearly school garden

- An “Eco Room” where students can understand life cycles and growth patterns as they monitor and groom greenhouse plants, and practice in the growth and release of butterflies. The Eco Room features two tons of recycled car tires as a vivid green and red landscape, a grow wall, and a butterfly hatchery.

For more information go to https://brookside.paramountindy.org/